Greetings, friends and family! Magandang umaga, po! I apologize that I have not updated this blog in quite a while. I sat down and began a post a little over a week ago, but did not have time to finish it. I wanted to at least try to post something else before going home. Oh well, sometimes we can’t always do what we want. I hope that this will do! For the majority of you, this will be the first time you hear that I am….(guess what)…. home!

The Philippines is a perfect 12 hours ahead of Eastern Daylight Time (EDT). This actually made it easy for me whenver I wanted to call home, because I knew I could almost always reach my family during my morning. So because the Philippines is 12 hours ahead, jet-lag also takes a little while to get over. (After going to bed last night around 10:00, I woke up at 3:30am)!

On Wednesday morning, Philippine Time (PHT), I woke up at 3:30am in order to drive to the airport with the other two Food for the Hungry interns so that they could catch their 7:45 flight and then I could catch my flight shortly after that at 9:00am. I then flew to Tokyo which is almost a 5 hour flight, and had a 3 hour layover. I then flew to Chicago, which was a little less than a 12 hour flight, and had a 4 hour layover, during which I cleared customs and found my way to the gate for my final flight home to Greenville, SC. That flight was around 2 hours, and I arrived at 10:00pm, Wednesday night, EDT.

As I sit down to write this post this morning (actually, I am rewriting the first part of this because I accidentally deleted some of it), it is hard to believe that I have been in the Philippines for the past three months. In one way, it feels like just yesterday that I was packing up to leave. But then again, it feels like I have been gone for over 100 years.

I feel that I have greatly benefited from my experience in the Philippines this summer, and I will really miss it (especially the food)! In addition to the academic side of learning about the Microenterprise Development (MED) livelihood interventions that Food for the Hungry/Philippines implemented into their communities, I feel that I also benefited greatly from the experiences, both mentally, emotionally and spiritually. I feel that God used my experience this summer to help me critically think about how he will lead me in the future after school. This internship has helped me, and will continue to help me, think about my career. I now have more certainty that this type of work is something I would be very much interested in pursuing for my life.

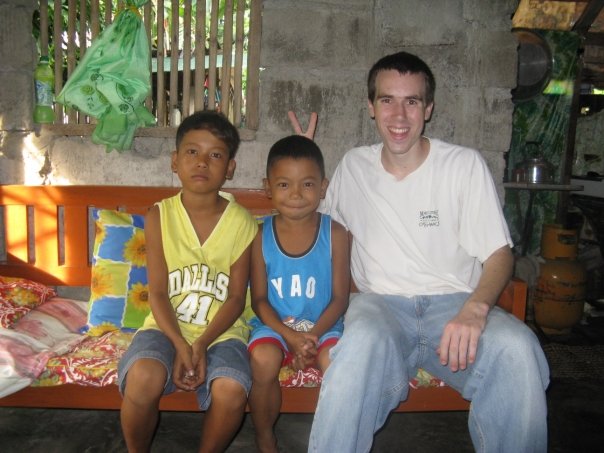

I want to post some of my favorite pictures from the Philippines. Some of these I think I may have uploaded in previous posts to my blog, but some of them are also new. (My camera is working again now! After emailing a photographer friend of mine and then fiddling around with it, everything started to eventually work again except the lens cover, which was constantly covering the lens 1/2 way, regardless of if the camera was on or off. So I took a small piece of paper and wadded it up and jammed it down inside to keep the lens cover open so that I can take pictures)!

* Please don’t use any of my photos without my prior permission.

As some of you may recall, I went to the Philippines primarily so that I could fulfill my academic course work & requirement. My major at Covenant College requires that I spend at least 12 weeks on a research internship. My research was primarily focused on the livelihood programs that Food for the Hungry Philippines (FH/Phil) implemented into their communities. As a result, throughout the summer, I wrote weekly logs and 6 papers including my final Research Findings paper. I also gave an oral report to FH/Phil about my research findings.

I will finish this blog update by copying my final research paper. But before I do, let me once again say “thank you” to everyone who has supported me in anyway during this summer.

In Christ,

David White

Livelihood and Savings Groups as FHI-Philippines MED Interventions:

Written Report of Research Findings

David White

Covenant College & Food for the Hungry Philippines

August 1st, 2008

I. Introduction

From May 14th through August 6th, 2008, I lived and worked in the Philippines doing research for Food for the Hungry Philippines (FHI). My original goal of research was to learn how FHI introduced livelihood programs into their communities, and how these Microenterprise Development (MED) interventions were successful. I wanted to identify the areas in which FHI was successful, and to explain why. I wanted to learn what worked, for whom, under what circumstances.

Microenterprise development (MED) focuses on helping very small businesses with “management, accounting, production, business infrastructure, product development, and market access.” It “is a development strategy that provides a broad package of financial services … as well as other business development services” (Bussau & Mask, 2003). Microfinance on the other hand, which could be a part of MED, is “financial services (savings, loans, insurance) that enable the poor to obtain lump sums [of money] for emergencies, life cycle needs, and opportunities for household investment” (Chalmers Center).

In addition to looking for ways in which FHI was successful in their MED livelihood interventions, I wanted to learn about the projects that were not successful. In studying these projects, it was my goal to indentify ways in which the projects could be improved, and to explain why they did not work. In short, I wanted to learn what did not work, for whom, under what circumstances.

Finally, I learned about some of the savings groups that FHI helped form in some of their communities. Savings groups, which are considered a kind of microfinance usually can not be used to start and sustain livelihood projects. Instead, they are usually a great help in providing funds for emergencies, life cycle needs and investment opportunities, as I indicated earlier. While this was certainly not where the majority of my work was focused upon, it greatly helped to learn about this kind of microfinance (which of course can be a part of doing MED). With this knowledge, I have been better able to analyze how and why FHI was successful, and determine areas in which FHI can improve upon.

The majority of my research consisted of learning how the livelihood projects that FHI introduced into their communities has brought improvement to the lives of individuals. While this is only a part of MED, it is the first and central part of doing MED. Without any livelihood projects to develop, there is no MED!

In addition to learning about these MED interventions, I was also able to learn about the Child Development Program (CDP) that FHI operates in the Philippines. Because the CDP is the primary work that FHI does in their communities, I quickly learned that other FHI programs like MED stem from the communities’ involvement in the CDP. As a result, it is hard to separate the MED from the CDP in many cases, and the effectiveness of the combined programs (where MED does exist) must be taken into account.

The main method of data gathering for my research was the interview. I conducted several semi-formal and informal interviews during my 12 weeks in the Philippines. The vast majority of these interviews were individual interviews in areas where FHI has already phased and is no longer at work and through these, I obtained a lot of data. However, the few group interviews that I conducted were also extremely helpful and informative. Although I mainly worked in areas where FHI has already left, I was also able to learn about one area where FHI is still working.

II. Research Results

The mission of FHI is “to equip, link and mobilize churches, leaders and families in overcoming all forms of human poverty by living in healthy relationships with God and his creation” (Community Transformation). In this statement, God’s “creation” includes not only the environment, but also the people that we interact with (our selves and our community). FHI has done well in living out this mission of wholistic transformation and helping individuals improve their relationships with God, themselves, others (friends, family and enemies) and the environment.

In order to achieve this mission, FHI has introduced several programs into the communities which they seek to do sustainable development. The four programs that I was able to learn about were the Child Development Program (CDP), the College Assistance Scholarship, the livelihood interventions, and the savings groups. But of course, since my research focused on MED (including microfinance), I mainly learned about the livelihood interventions and savings groups that FHI helped start.

The impact of the livelihood programs in a community can not be fully measured because of their coexistence with the CDP. While this is the program from which all other programs normally stem, it is also the oldest and original program of FHI. For example, in one community, FHI began work in 1993 with their CDP. However, it wasn’t until 2004 that livelihood programs were introduced.

There are several livelihood projects that FHI helped start in their communities. I observed four different livelihood projects in my research, which were pig production, poultry production, sari-sari stores, and snack making. However, the only livelihood project that I found in every community that I observed extensively was the pig production. These livelihood projects produced many results.

In the majority of the instances that I found pig production, beneficiaries raised pigs for meat (as opposed to raising pigs for breeding). Pig production was also the most common livelihood project in each of the communities. In one community, for example, I found 10 families that raised pigs, as opposed to only 4 families who raised poultry (2 families raised both pigs and poultry, which leaves only 2 families that only raised poultry). In another community, I found that both women I interviewed raised pigs.

Overall, I interviewed a total of 16 participants in the hog raising projects. Out of these, 6 participants chose to use one pig for breeding (some of these had more than 1 pig, and raised another one for meat). However, only 3 of these pigs were successful in producing. The other 3 became sick or were unable to produce piglets, so the owner ended up having to sell the pig.

In addition to the 3 pigs that were unable to breed, I found that two other people were unable to properly care for their pigs when they got sick. One woman suggested that having an animal expert, or a vet, available when needed, would be beneficial because most families do not have the expertise or knowledge to help a pig when it gets sick. The inability to care for, and non-access to expertise for, taking care of the pigs when they experienced problems affected all 5 people.

Besides experiencing problems with the health of the pigs, I learned that the people were greatly affected by the market conditions of raising and selling the pigs. For example, I learned that sometimes when the pig is ready to be sold for meat, the buyer refuses to pay the amount that was originally agreed upon (usually it takes 4-6 months until a pig weighs the amount it should weigh in order to be sold. This amount of time usually depends on how the pig is fed). However, because the pig’s weight indicates it is ready to be sold, it is not profitable for the owner to keep the pig any longer. So the person is forced to sell at the lower price.

The poultry production livelihood project was also interesting to study. Overall, I interviewed 5 individuals who had raised poultry, as well as 1 group (some of the individuals I interviewed were also in the group interview). While individual people have personal reasons to start in any sort of livelihood project, I found that the group also had interesting reasons to start work in poultry. I learned that raising poultry takes neither much time nor much land. This was very advantageous, because it meant that the families could continue in their regular jobs while raising the chickens as a side business. Beyond this, the reasons that members of the group decided to raise poultry were to have additional income, to help the poor members in the group, to uplifting the status of living, to have a permanent source of income, to be known as a stable group, and finally, to achieve the vision of the group (“to improve the spiritual and physical life…”).

I learned that in the poultry projects, commercial-grade chickens are raised for a 35-day period (1 cycle) and then are sold to the chicken farms. The individuals within the group project in one community were mainly successful for the first two cycles. I learned that each person kept a total of 50 chicks, and earned an average of P2,400. Like the weight of the pigs beyond the target weight, it is not profitable to keep the chicks longer than 35 days. In the cycles after the 2nd (most of my informants participated in 3 cycles, and some participated in a 4th), the market conditions prevented them from making a profit. Like some of the times when the pigs were sold, the buyer for the poultry only offered a low amount.

The other two livelihood projects that I studied, the sari-sari store, and snack making were also able to produce results. As part of relief-assistance after a disaster, the sari-sari store owner and snack making person that I interviewed had received a lump sum of money from FHI which was ½ loan, ½ grant. Both were able to successfully pay back the loan portion within three months! Before being started, the sari-sari store owner and snack maker consulted with FHI to make sure there was demand in their area of work. Thesnack maker originally also wanted to start a sari-sari store, but FHI wouldn’t let her because there were already too many stores in the community. So, she thought about making snacks and selling them in the local school. While the sari-sari store has been successful and continues to operate (without FHI assistance any longer), the snack maker was forced to quit her business because the national government banned all food vendors from selling inside the schools, because a student recently got food poisoning and died.

While beneficiaries were not required by FHI to start a livelihood project, of course, the people in the communities that I researched had many financial needs that helped prompt them to start. The most common economic concern that I found was that people needed money for their children’s education. Other important economic concerns included providing food for the family, and in some cases, obtaining medicine or paying medical bills, or to simply have additional, supplemental income for general living expenses, emergencies, or life-cycle needs.

Besides the economic benefit from starting a livelihood project, there were other reasons that people joined. Some people were encouraged to participate in FHI-sponsored livelihood because they already had prior experience in the livelihood being offered. Finally, in one instance, livelihood was a group initiative, and members of the group wanted to promote the vision of, and encourage and help other members in the group.

In every instance of pig production that I found, and in most cases of the other livelihood projects, my interviewees reported making a profit. The income that was generated from all four livelihood projects was used for several things. The majority of the people I interviewed used the extra income for their children’s education and for daily expenses for food. In one community, the participants’ children have to pay for transportation for school, and the livelihood projects helped pay for this. Other uses of the extra money were medical expenses for the family, house renovations, wedding, electric bills and utilities, and primary job expenses on the farm.

The savings groups, as I have already mentioned, are generally used as a form of microfinance to help people obtain lump sums of money for emergencies, life cycle needs, and special occasions (like weddings), and are not usually used to help support or start a livelihood microenterprise. The few savings groups that I did learn about also had success.

I learned that in every savings group that is formed by FHI, a seminar is first given to the community, and members of the savings group are required to attend. Here, the 5Ms of microfinance are stressed as very important. The 5Ms of microfinance are defining the Mission of the group, defining the Membership of the group, deciding who will keep the Money in the savings group, deciding upon who will Manage and govern the group, and finally, deciding how the Monitoring system will take place (In addition to this information which I received from an informant, refer to Chalmers Center).

In one community that I briefly studied, I learned that several people in the community participated in 3 different savings groups started by FHI. These people, whom I interviewed in a group interview, said that they joined for emergency purposes. However, I later learned that they were required by FHI to participate in the savings group. Thus, I can never be sure if the participants would have chosen to participate on their own. All three groups started in May, 2007, and ended that December. I learned that when the groups ended in December, 2007, the participants were able to use the lump sums for many things. One woman used the money for her child during the Christmas season to buy clothes. Another woman used her lump sum for the Christmas holiday as well as for school materials. Yet another woman used the lump sum for paying electric and other bills, as well as to pay off debts. As can be seen, the savings groups helped the women in many ways.

In addition to the economic profit that people made from the livelihood projects, and the help that the lump sums of money from the savings groups were, the people reported that they were helped in other ways. As I mentioned earlier, FHI strives to help people live in healthy relationships with God, themselves, others, and the environment. Of course, since FHI is a Christian organization, their first goal in operating their programs like the MED interventions is to help people live in healthy relationships with God.

When people become members of the CDP, livelihood program or savings group, they are required by FHI to participate in a weekly bible study. Through these efforts, FHI has seen some success in helping people improve their relationships with God. For example, in one community, I found that 11 out of the 13 people I interviewed became regular church goers only after FHI arrived and began work in their community (the other two were already attending a church regularly). In another community I researched, one of the two women I interviewed became a regular church participant only after FHI arrived. However, as one involved woman said, the program was not always successful in developing the parents, because the parents wanted the material benefits and looked for ways to get out of being involved in the bible studies and church.

In addition to helping people live in healthy relationships with God, FHI also wants to help people live in healthy relationships with themselves. As Bryant Myers points out in his book Walking with the Poor, all humans have a marred identity that prevents them from living up to their God-given potential. A good example of how FHI has been successful in this is the story of Ate Mary (name changed to protect identity). Ate Mary says that because of the programs FHI offered, she was encouraged to attend church and the bible studies. She was baptized as a believer, and felt that even though she still experienced problems, she now had the strength to face them. She says “I can’t forget FHI because they helped me develop myself.”

FHI also wants to help people have a healthy relationship with others. This has also seen some success, and like all four main relationships, this is very good and important to focus on. In one community, I found that women who had been living together for over ten years did not begin to know each other or spend time with each other until the savings group was started recently. The members of the group learned the value of saving, and a good relationship was built between the mothers involved.

Finally, FHI wants to help people live in a healthy relationship with God’s creation. This is Biblical, as Colossians 1:15-17 indicates that Christ made all things and that all things hold together through him. We know that the people of a community are the primary stewards of it, and that God has mandated that humans care for our environment. Part of this, of course, can be seen through the interaction that community members have with the environment and their jobs as farmers, fishermen, or even as members of the pig production or poultry production livelihood projects.

III. Further Research

As I conducted my research and especially as I analyzed my data, I was reminded of something that I thought about early in my research and data gathering. The importance of the impact that the CDP makes on the support programs (like the MED and microfinance) can not and should not be ignored. If I had had more time to spend researching, this is one area that I would have attempted to focus on.

In addition to the additional research on the economic and non-financial impact that the CDP makes on a given community, I think that it would have also been beneficial to research how FHI has been successful and what areas it could improve upon in keeping a community from becoming “dependent” on FHI. This avoidance of dependency is very important to FHI, and it would be interesting to study how a community begins to “help itself” once FHI leaves.

An important lingering question that I had for many of the people that I interviewed was “why did they choose to get involved in the livelihood projects to begin with?” Finding out what the economic needs were, and what the personal reasons were that people had for joining a livelihood project would have been very beneficial in my research (in the instances where I did not learn this information).

IV. Conclusions

MED and microfinance can sometimes be very complicated and can sometimes be hard to effectively implement. However, when they are introduced into a community responsibly and appropriately, they can produce many good results. Throughout my research in the Philippines, I studied four different livelihood projects as well as a few savings groups.

While I found that most of the time, the livelihood projects and savings groups were successful in providing economic and other benefits to the beneficiaries, I found that the biggest problem to livelihood was the market conditions. The beneficiaries of both the pig production and poultry production sometimes had problems because the price of feed become expensive and the buyer would only offer a low price. Despite these problems, the MED and microfinance were still successful.

Even though the market conditions sometimes created problems, there were many economic benefits from the livelihood projects and savings groups. Both the extra income from the livelihood projects and the lump sums of money from the savings groups that people obtained, helped people to (for the majority of the time) pay for school fees and pay for daily food needs of the family. In addition, I found that the income from the livelihood projects were sometimes used for medical expenses, house renovations, farm and other on-the-job expenses of the regular job, among others.

In addition to the economic benefit that people experienced in their livelihood projects and savings groups, I found that all four key relationships were usually improved. One’s relationship to God is the most important, and I found that often times, the programs of FHI led many people to the Lord, and they became active members in the church. I also found that the “marred identity” that people have of themselves was improved. The relationships that people have with their community members was affected for the better. And finally, one can see a difference in the way people related to their environment.

Overall, depending on how one would define “success,” I would say that the livelihood projects and savings groups were successful in meeting FHI’s goal of wholistic transformation. We can see this through both the economic and non-material benefits that people have experienced. These benefits will undoubtedly affect the community the people are in for a long time to come.

V. Bibliography

Bussau, D., & Mask, R. (2003). Christian Microenterprise Development. Waynesboro, GA: Regnum Books International.

Chalmers Center. Distinguishing Characteristics of Providing, Partnering, and Promoting Microfinance. (Published Date Unknown). Retrieved July 2008. Web site: http://scots.covenant.edu/depts/chalmers/Eco448/Eco448 Recommended Readings/Distinguishing Characteristics of 3 Ps.doc.

Food for the Hungry International Human Resource Development. (2005). Welcome to Food for the Hungry International An Orientation to our Ministry and Corporate Identity. Bangkok Thailand: Food for the Hungry International.

Food for the Hungry Philippines. (Published Date Unknown). Community Transformation in the Philippines. Brochure. Manila, Philippines.

Lamigo, C. (2008). Grant Assistance Report. Manila, Philippines: Food for the Hungry Philippines.

Myers, B. (1999). Walking With the Poor. New York: World Vision.

David,

Really enjoyed your final update and your paper! What a terrific opportunity and I know from speaking with some of the folks from FHUS that FH Phillipines very much enjoyed having you there. Can’t wait to see what the next chapter will be. God bless you!

Marty